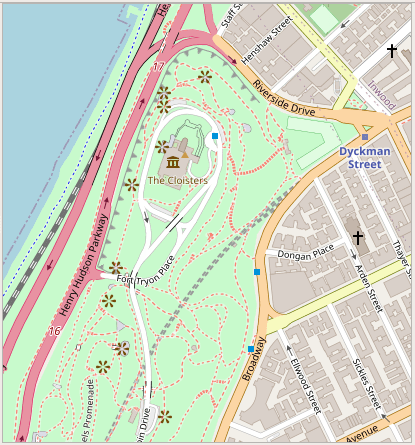

A couple years ago I wrote a post that demonstrated how to use the QuickOSM plugin for QGIS to easily extract features from the OpenStreetMap (OSM). The OSM is a great source for free and open GIS data, especially for types of features that are not captured in government sources, and for parts of the world that don’t possess a free or robust GIS data infrastructure. I’ve been using ArcGIS Pro more extensively in my new job and was wondering how I could do the same thing: query features from the OSM based on keys and values (denoting feature type) and geographic area and extract them as a vector layer. I’m looking for straightforward solutions that I could use for answering questions from students (so no command line tricks or database stuff). In this post I’ll cover three approaches for achieving this in ArcGIS Pro, with references to QGIS.

File Approach

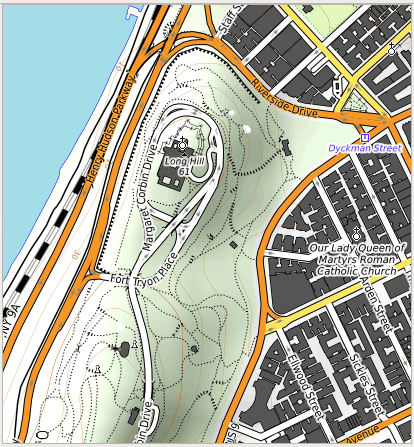

The most straightforward method would be to export data directly from the main OSM page by zooming into an area and hitting the Export button. This is a pretty blunt approach, as you have to be zoomed in pretty close and you grab every possible feature in the view. The “native” file format of OSM is the osm / pbf format; .osm is an XML file while .pbf is a compressed binary version of the osm. QGIS is able to handle these files directly; you just add them as a vector layer. ArcGIS Pro cannot. You have to download and install a special Data Interoperability extension, which is an esoteric thing that’s not part of the standard package and requires a special license from your site license coordinator.

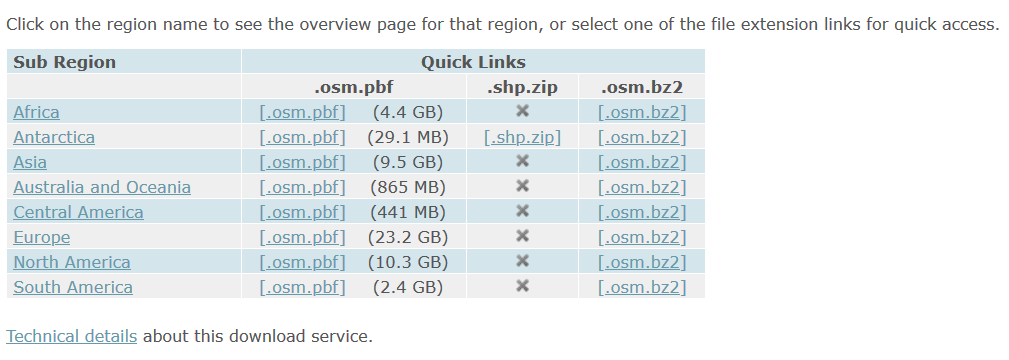

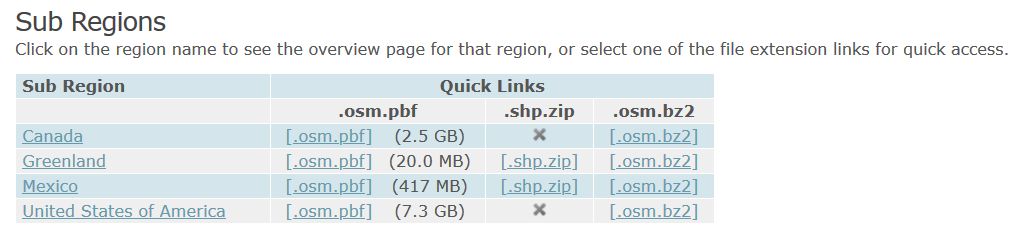

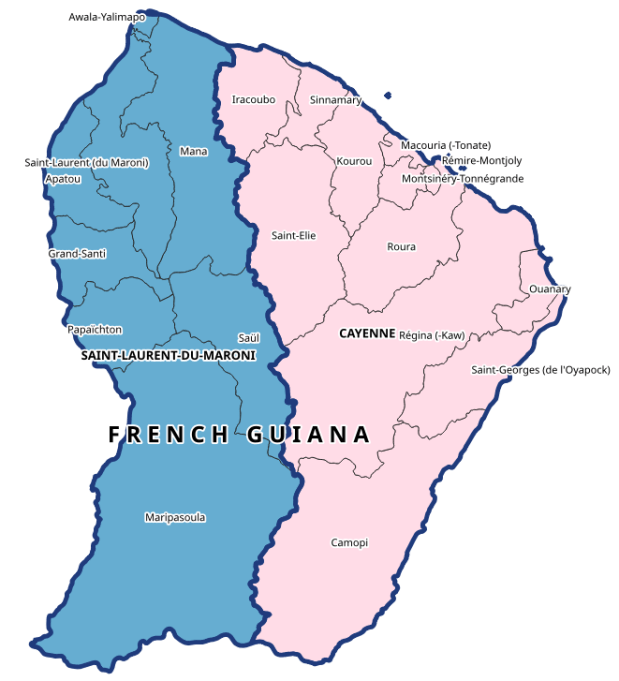

A better and more targeted approach is to download pre-created extracts that are provided by a number of organizations listed in the OSM wiki. I started with Geofabrik in Germany, as it was a source I recognized. They package OSM data by geographic area and feature type. On their main page they list files that contain all features for each of the continents. These are enormous files, and as such they are only provided in the osm pbf format as shapefiles can’t effectively handle data that size. Even if you downloaded the osm pbf files and added them to QGIS, the software will struggle to render something that big.

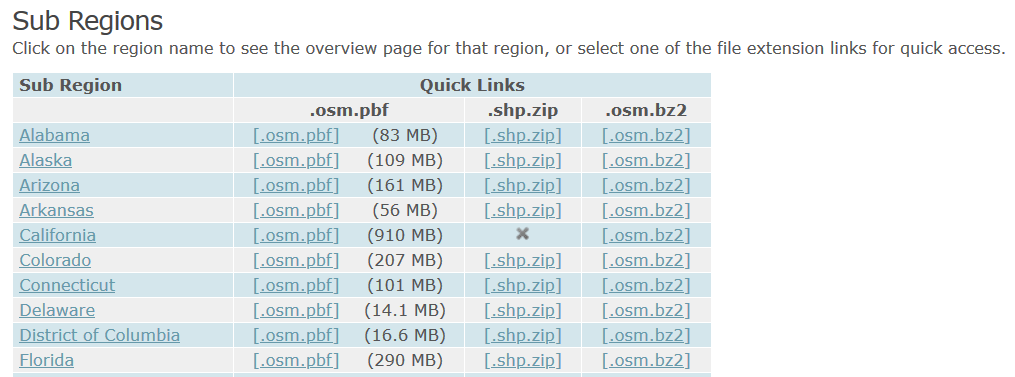

But all is not lost; Geofabrik and many other providers package data in a shapefile format for smaller areas, provided that the size and number of features is not too great. For instance, on Geofabrik’s download page if you click on North America you’re presented with country extracts for that continent (see images below). You can get shapefiles for Greenland and Mexico, but not Canada or the US as the files are still too big. Click on US, and you’re presented with files for each of the states. No luck for California (too big), but the rest of states are small enough that you can get shapefiles for all of them.

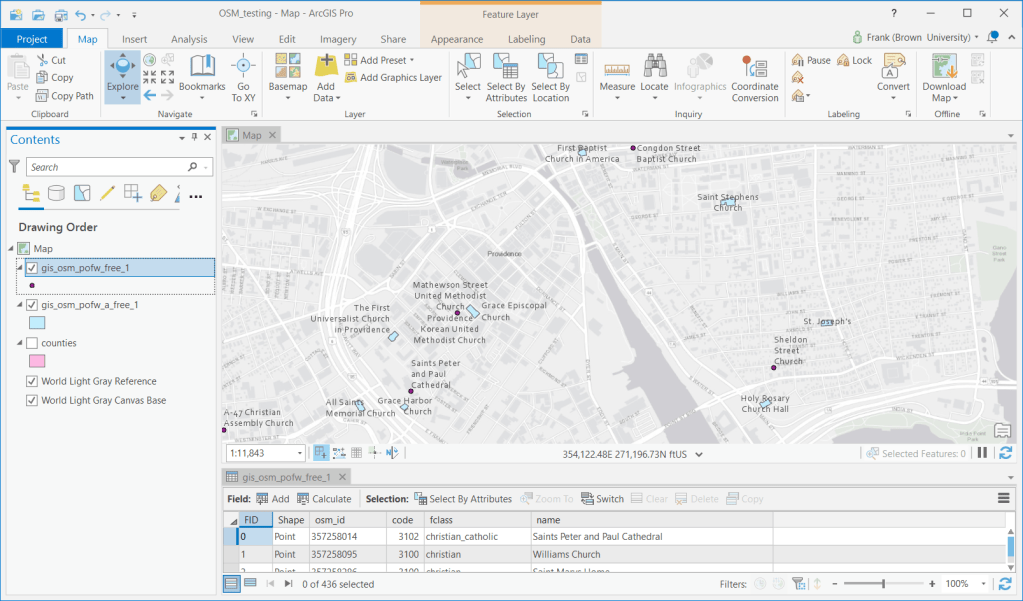

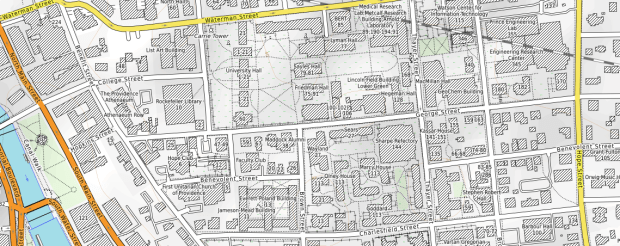

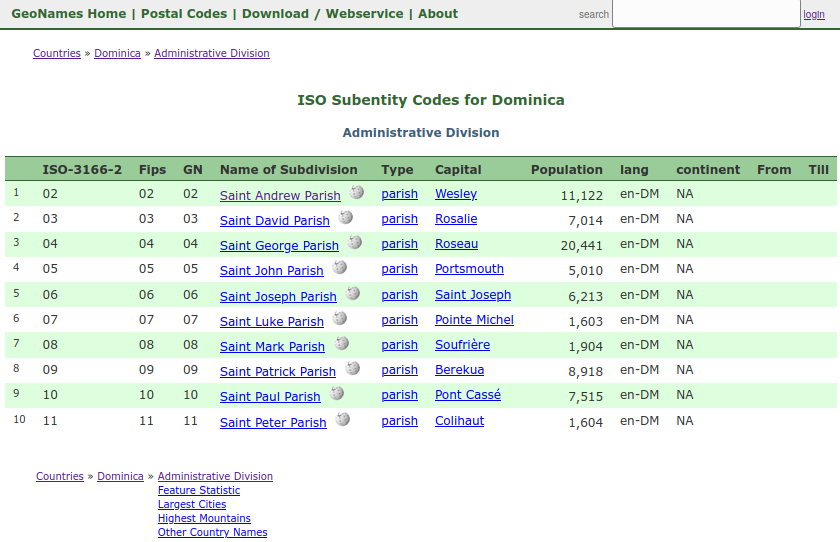

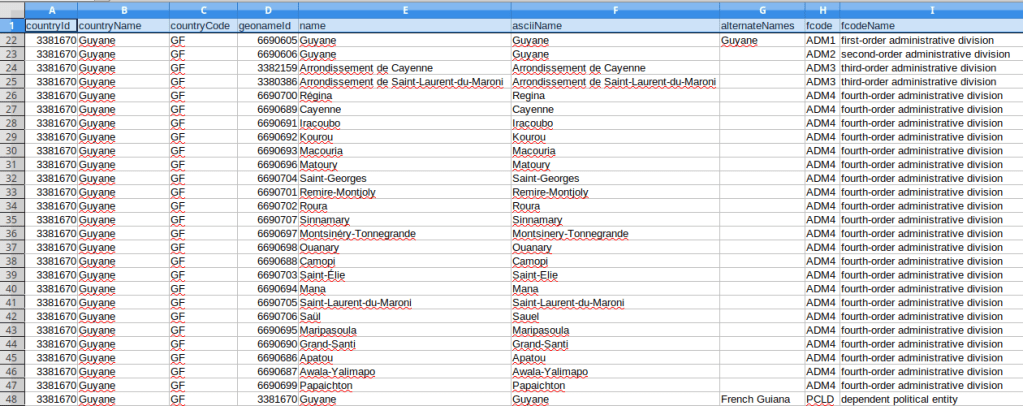

I downloaded and unzipped the file for Rhode Island. It contains a number of individual shapefiles classified by type of feature: buildings, land use, natural, places, places of worship (pofw), points of interest (pois), railways, roads, traffic, transport, water, and waterways. Many of the files appear twice: files with an “a” suffix represent polygons (areas) while files without that suffix are points or lines. Some OSM features are stored as polygons when such detail is available, while others are represented as points.

For example, if I add the two places of workship files to a map, for some features you have the outline of the actual building, while for most you simply have a point. After adding the layers to the map, you’ll probably want to use Select by Attribute to select the features you want based on OSM tags with keys and values, and Select by Location in conjunction with a separate boundary file to pull data out for a smaller area. The Geofabrik OSM attribute table is limited to basic attributes: an OSM ID, feature code and class, and name. It’s also likely that you’ll want to unify the point and polygon features of the same type into one layer, as they’re usually mutually exclusive. Use the Centroid (Polygon) tool in the toolbox to turn the polygons into points, and the Merge tool to meld the two point layers together. In QGIS the comparable tools under the Vector menu are Centroids and Merge Vector Layers. WGS 84 is the default CRS for the layers.

Geofabrik is just one option. There are several others and they take different approaches for structuring their extracts. For example, BBBike.org organizes their layers by city for over 200 cities around the world, and they provide a number of additional formats beyond OSM PBF and shapefiles, such as Garmin GPS, GeoJSON, and CSV. They divide the data into fewer files, and if they don’t compile data for the area you’re interested in you can use a web-based tool to create a custom extract.

Plugin Approach

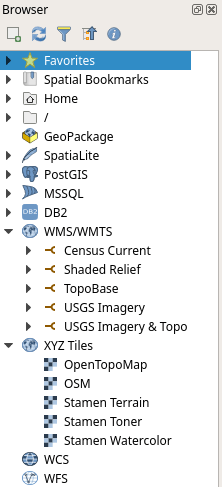

It would be nice to use a plugin, as that would allow you to specify a custom geographic area and retrieve just the specific features you want. QuickOSM works quite nicely for QGIS. Fortunately there is a good ArcGIS Pro solution called OSMquery. It works for both Pro and Desktop, tested for Pro 2.2 and Desktop 10.6. I’m using Pro 2.7 and the basic tool worked fine. It’s well documented, with good instructions for installation and use.

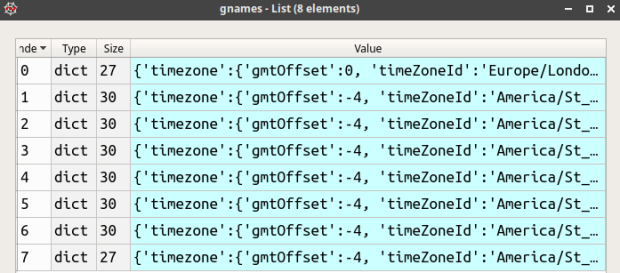

The plugin is written in Python and you add it as a tool to your ArcToolbox. Download the repo from the OSMquery GitHub as a ZIP file (click the green code button and choose Download ZIP). Save it in or near your ArcGIS project folders, and unzip it. In Pro, go into a project and open a Catalog Pane in the View ribbon. Right click on Toolbox to add a new one, and browse to the folder you unzipped to add the tool. There are two scripts in the box, a basic and an advanced version. The basic tool functioned without trouble for me. The advanced tool threw an error, probably some Python dependency issue (I didn’t investigate as the basic tool met my needs).

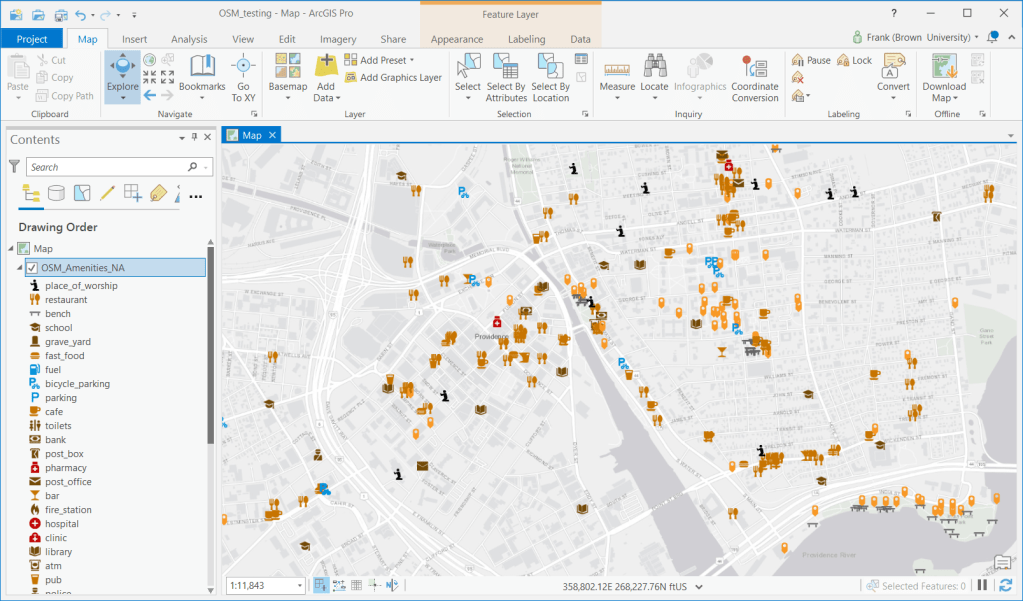

In the basic tool you choose the key and value for the features you want to extract; the dropdown menu is automatically populated with these options. For the geographic extent you can enter a place name, or you can use the extent of the current map window or of a layer in the project, or you can manually type in bounding box coordinates. Another nice option is you can transform the CRS of the extracted features from WGS 84 to another system, so it matches the CRS of layers in your existing project. Run the tool, and the features are extracted. If the features exist as both points and polygons, you get two separate files for each. If you choose, you can merge them together as described in the previous section; this is a bit tougher as the plugin approach yields a much wider selection of fields in the attribute table, and not all of the point and polygon attributes align. With the Merge tool in Pro you can select which attributes you want to hold on to, and common ones will be merged. QGIS is a bit messier in this regard, but in my earlier post I outlined a work-around using a spatial database.

Web Feature Service

This initially seemed to be the most promising route, but it turned out to be a dud. Like QGIS, Pro allows you to add OSM as a tiled base map. But ESRI also offers OSM as a web feature service: by hitting Add Data on the Map ribbon and searching the Living Atlas for “OpenStreetMap” you can select from a number of OSM web feature services, organized by continent and feature type. Once you add them to a map, you can select and click on individual features to see their name and feature type. The big problem is that you are not allowed to extract features from these layers, which leaves you with an enormous and heterogeneous mix of features for an entire continent. You can interact with the features, selecting by attribute and location in reference to other spatial layers, but that’s about it.

In Summary

I would recommend taking the step of downloading the OSMquery plugin for ArcGIS Pro if you want to take a highly targeted approach to OSM feature extraction (for QGIS users, enable the QuickOSM plugin). This approach is also best if you can’t download a pre-existing extract for your area because it’s too large or has too many features, and if you want to access the fullest possible range of attribute values. Otherwise, you can simply download one of the pre-created extracts, and use your software to winnow it down to what you need (or if you do need everything, the file approach makes more sense). Since the file-based option includes fewer attributes, converting polygon features to points and merging them with the other point features is a bit simpler.

You must be logged in to post a comment.