There’s been a lot of turmoil emanating from Washington DC lately. One development that’s been more under the radar than others has been the modification or removal of US federal government datasets from the internet (for some news, see these articles in the New Yorker, Salon, Forbes, and CEN). In some cases, this is the intentional scrubbing or deletion of datasets that focus on topics the current administration doesn’t particularly like, such as climate and public health. In other cases, the dismemberment of agencies and bureaus makes data unavailable, as there’s no one left to maintain or administer it. While most government data is still available via functioning portals, most of the faculty and researchers I work with can identify at least a few series they rely on that have disappeared.

Librarians, archivists, researchers, professors, and non-profits across the country (and even in other parts of the world), have established rescue projects, where they are actively downloading and saving data in repositories. I’ve been participating in these efforts since January, and will outline some of the initiatives in this post.

The Internet Archive

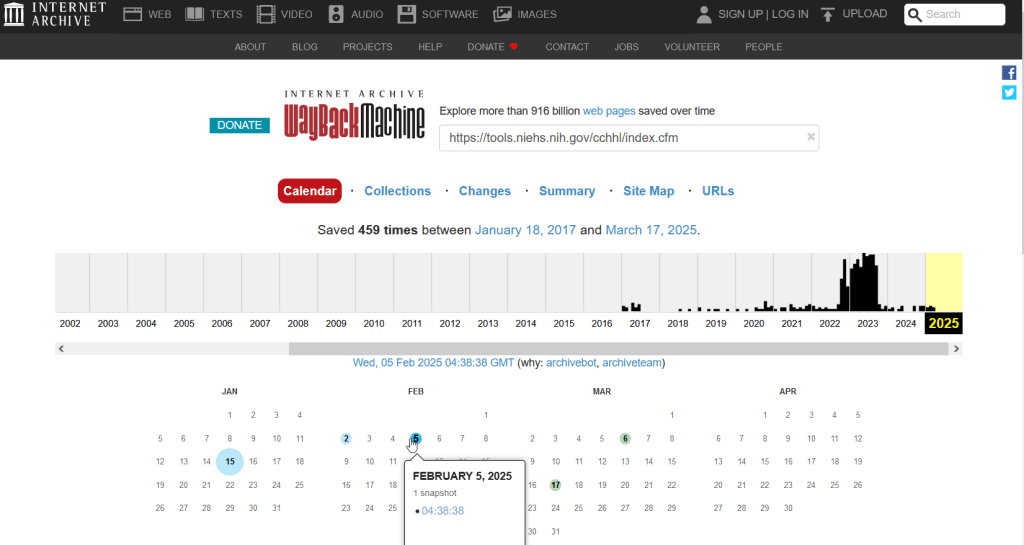

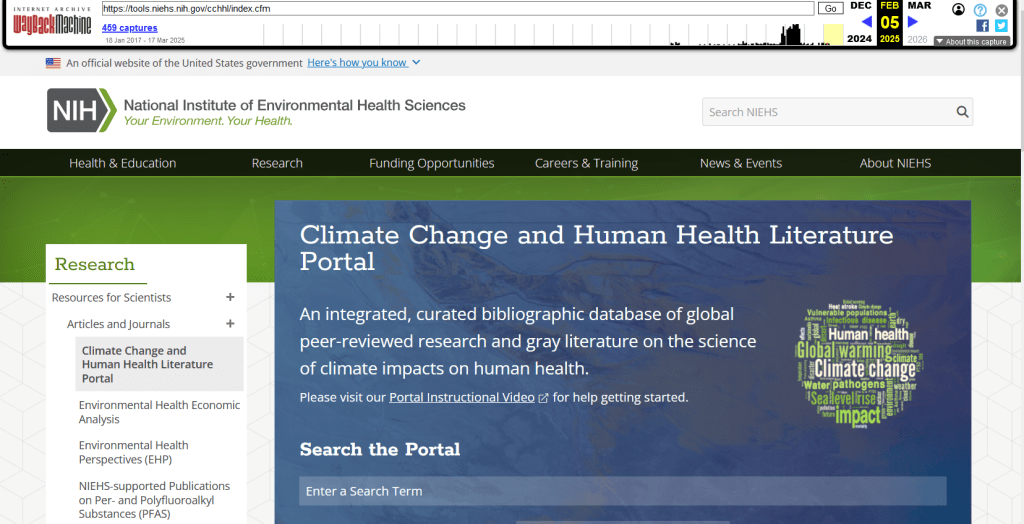

The place of last resort for finding deleted web content is the Internet Archive. This large, non-profit project has been around as long as the web has existed, with the goal of creating a historic archive of the internet. It uses web crawlers or spiders to creep across the web and make copies of websites. With the Wayback Machine, you can enter a URL and find previous copies of web pages, including sites that no longer exist. You’re presented with a calendar page where you can scroll by year and month to select a date when a page was captured, which opens up a copy.

This allows you to see the content, navigate through the old website, and in many cases download files that were stored on those pages. It’s a great resource, but it can’t capture everything; given the variety and complexity of web pages and evolving web technologies, some websites can’t be saved in working order (either partially or entirely). Content that was generated and presented dynamically with JavaScript, or was pulled and presented from a database, is often not preserved, as are restricted pages that required log-ins.

The Internet Archive also hosts a number of special collections where folks have saved documents, images, sound and video, and software. For example, you can find many research articles that are available in PubMed from the PubMed Central collection, a ton of documents from the USDA’s National Agricultural Library, and about 100 GB of data someone captured from the CDC in January 2025. A large project called the End of Term Archive was launched in 2008 to capture what federal government websites looked like at the end of each presidential term. The pages are saved in a special collection in the IA.

Data Rescue Project

Dozens of new data archiving projects were launched at the end of 2024 and beginning of 2025 with the intention of saving federal datasets. The Data Rescue Project is one of the larger efforts, which has been driven by data librarians and archivists with non-profit partners. Professional groups including IASSIST, ICPSR, RDAP, the Data Curation Network, and the Safeguarding Research & Culture project have been active organizers and participators. While this will be an oversimplification, I’ll summarize the project as having two goals

The first goal is to keep track of what the other archiving projects are, and what they have saved. To this end, they created the Data Rescue Tracker, which has two modules. The Downloads List is an archive of datasets that have been saved, with details about where the data came from and locations of archived copies. The Maintainers List is a catalog of all the different preservation projects, with links to their home pages. There is also a narrative page with a comprehensive list of links to the various rescue efforts, data repositories, alternate sources for government data, and tools and resources you can use to save and archive data.

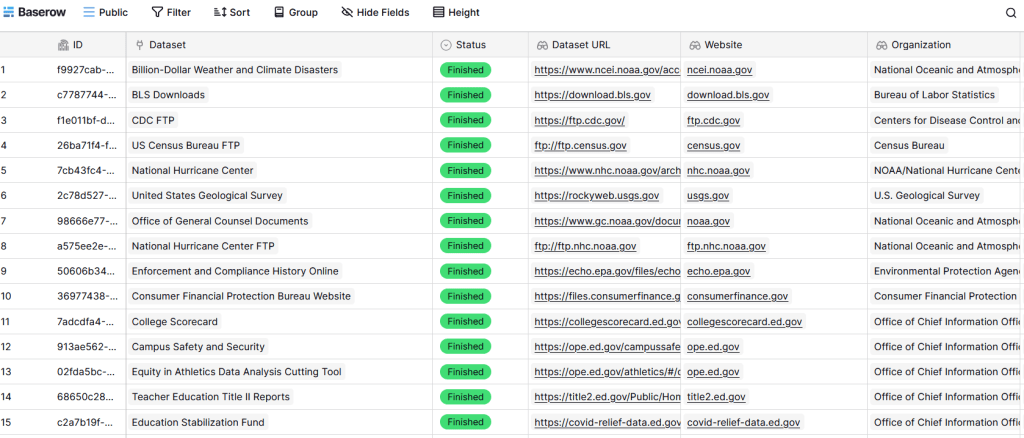

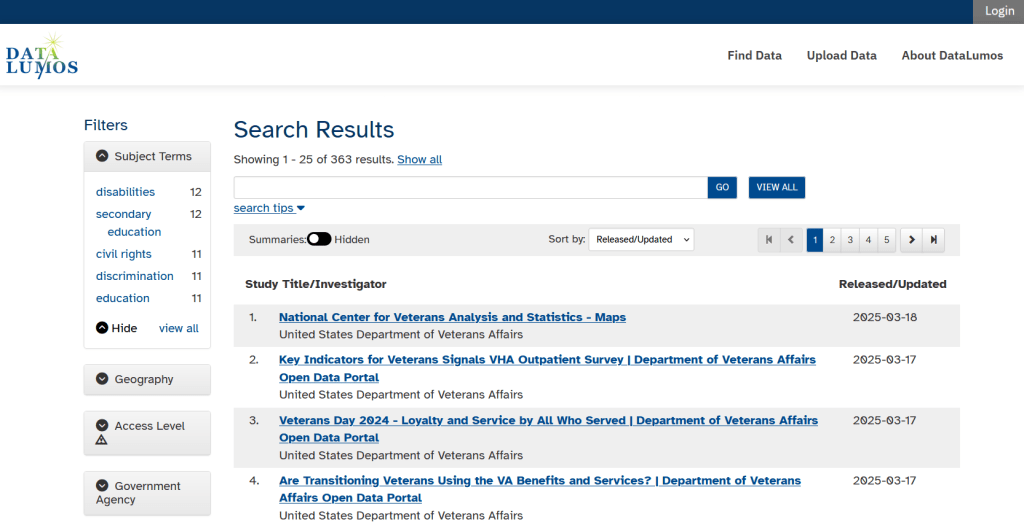

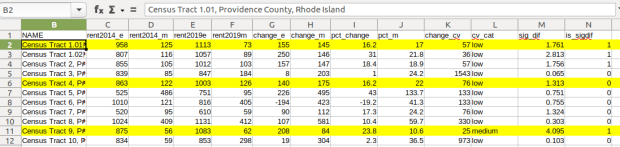

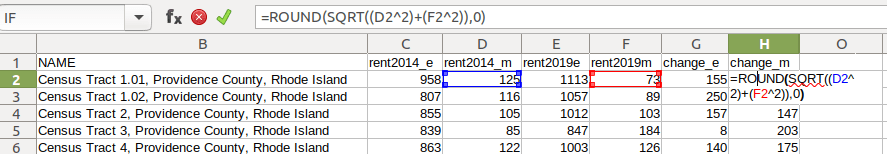

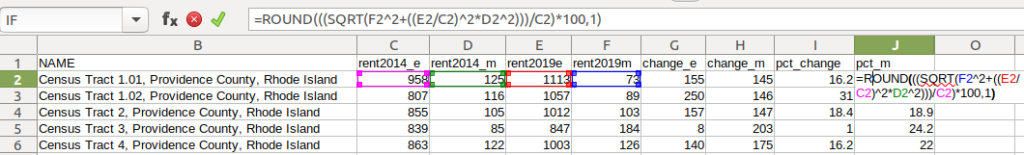

The second goal is to contribute to the effort of saving and archiving data. The team maintains an online spreadsheet with tabs for agencies that contain lists of datasets and URLs that are currently prioritized for saving. Volunteers sign up for a dataset, and then go out and get it. Some folks are manually downloading and saving files (pointing and clicking), while others write short screen scraping scripts to automate the process. The Data Rescue Project has partnered with ICPSR, a preeminent social science research center and repository in the US, at the University of Michigan. They created a repository called DataLumos, which was launched specifically for hosting extracts of US federal government data. Once data is captured, volunteers organize it and generate metadata records prior to submitting it to DataLumos (provided that the datasets are not too big).

Most of the datasets that DRP is focused on are related to the social sciences and public policy. The Data Rescue Project coordinates with the Environmental and Government Data Initiative and the Public Environmental Data Partners (which I believe are driven by non-profit and academic partners), who are saving data related to the environment and health. They have their own workflows and internal tracking spreadsheets, and are archiving datasets in various places depending on how large they are. Data may be submitted to the Internet Archive, the Harvard Dataverse, GitHub, SciOp, and Zenodo (you can find out where in the Data Rescue Tracker Download’s List).

Mega Projects

There are different approaches for tackling these data preservation efforts. For the Data Rescue Project and related efforts, it’s like attacking the problem with millions of ants. Individual people are coordinating with one another in thousands of manual and semi-automated download efforts. A different approach would be to attack the problem with a small herd of elephants, who can employ larger resources and an automated approach.

For example, the Harvard Law School Library Innovation Lab launched the Archive of data.gov, a large project to crawl and download everything that’s in data.gov, the US federal government’s centralized data repository. It mirrors all the data files stored there and is updated regularly. The benefit of this approach is that it captures a comprehensive amount of data in one go, and can be readily updated. The primary limitation is that there are many cases where a dataset is not actually stored in data.gov, but is referenced in a catalog record with a link that goes out to a specific agency’s website. These datasets are not captured with this approach.

If trying to find back-ups is a bit bewildering, there’s a tool that can help. Boston University’s School of Public Health and Center for Health Data Science have created a find lost* data search engine, which crawls across the Harvard Project, DataLumos, the Data Rescue Project, and others.

Beyond the immediate data preservation projects that have sprung up recently, there are a number of large, on-going projects that serve as repositories for current and historical datasets. Some, like IPUMS at the University of Minnesota and the Election Lab at MIT focus on specific datasets (census data for the former, election results data for the latter). There are also more heterogeneous repositories like ICPSR (including OpenICPSR which doesn’t require a subscription), and university-based repositories like the Harvard Dataverse (which includes some special collections of federal data extracts, like CAFE). There are also private-sector partners that have an equal stake in preserving and providing access to government data, including PolicyMap and the Social Explorer.

Wrap-up

I’ve been practicing my Python screen scraping skills these past few months, and will share some tips in a subsequent post. I’ve been busy contributing data to these projects and coordinating a response on my campus. We’ve created a short list of data archives and alternative sources, which captures many of the sources I’ve mentioned here plus a few others. My library colleagues in the health and medical sciences have created a list of alternatives to government medical databases including PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov

Having access to a public and robust federal statistical system is a non-partisan issue that we should all be concerned about. Our Constitution justifies (in several sections) that we should have such a system, and we have a large body of federal laws that require it. Like many other public goods, the federal statistical system contributes to providing a solid foundation on which our society and economy rest, and helps drive innovation in business, policy, science, and medicine. It’s up to us to protect and preserve it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.