Last year I wrote about my stamp collecting hobby in a piece that explored maps and geography on stamps. Since it was well received, I thought I’d do a follow-up about geography and postmarks on stamps. I also thought it would be a good time to feature some “lighter” content.

Many collectors search for lightly canceled stamps to add to their collections, where the postmark isn’t damaging, heavy, or intrusive to the point that it obscures what’s depicted on the stamp, while others will only collect mint stamps. But the postmark can be interesting, as it reveals the time and place where the stamp did its job, and may also convey additional, distinct messages that tie it to the location where it began its journey.

Consider the examples below. Someone was up late mailing letters, at 10:30pm in Edinburgh, Scotland on Jan 12, 1898, and just after midnight at the Franco-British Exhibition in London on Aug 31, 1908. A pyramid looms and the sphinx peers behind a stamp postmarked in Luxor at some point at the end of the 19th century (based on when that stamp was in circulation). While Queen Victoria has been blotted out and the sphinx is obscured, these marks turn the stamps into unique objects which situate them in history.

I add stamps like these to a special album I’ve created for postmarks. I’ll share samples from my collection here; they won’t be illustrative of all postmarks from around the world, but reflect whatever I happen to have. I’ll also link to pages that provide information about particular series that were widely published and popular for collecting. Check out this introduction on stamp collecting from the National Postal Museum at the Smithsonian if you’d like a primer. They are also an excellent reference for US stamps.

Time and Place in Cancellation Marks

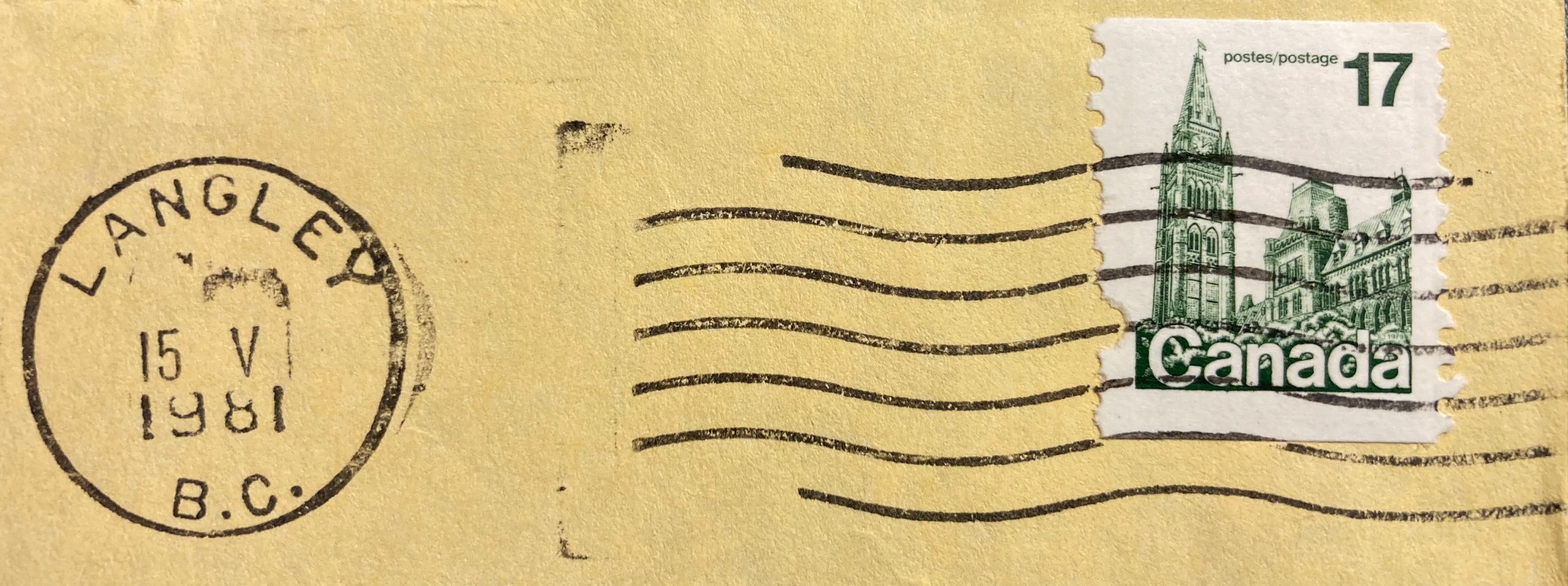

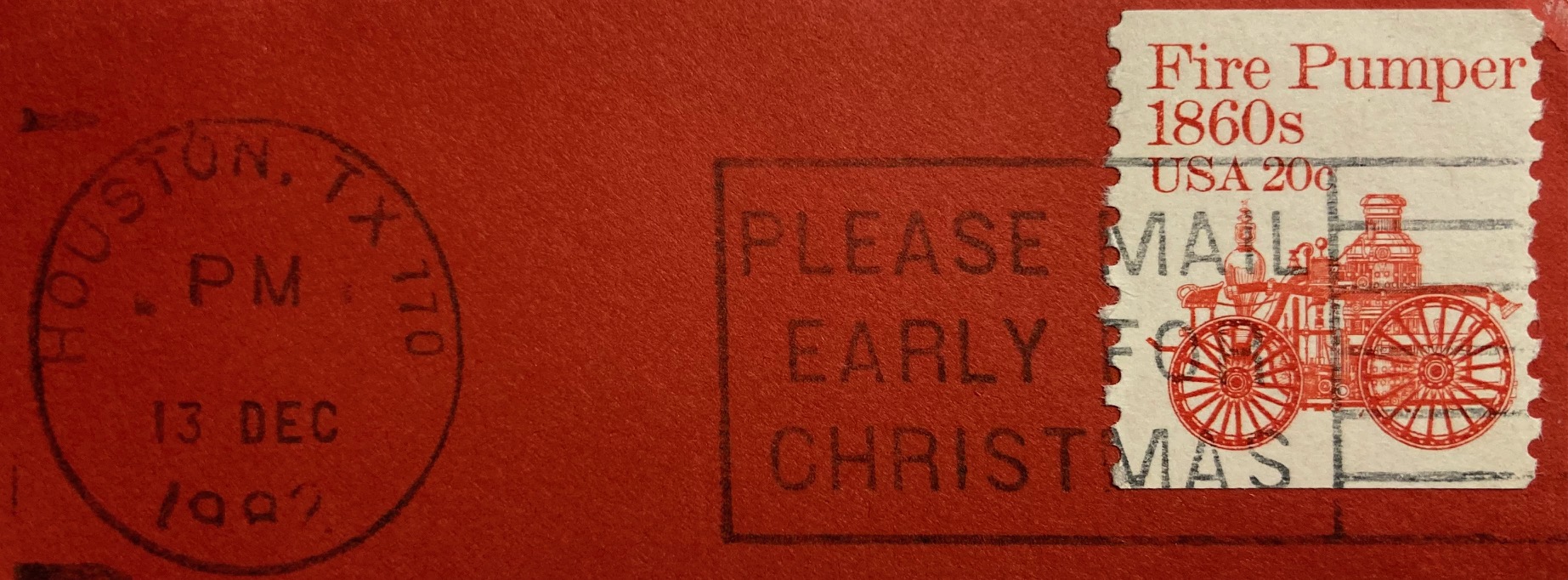

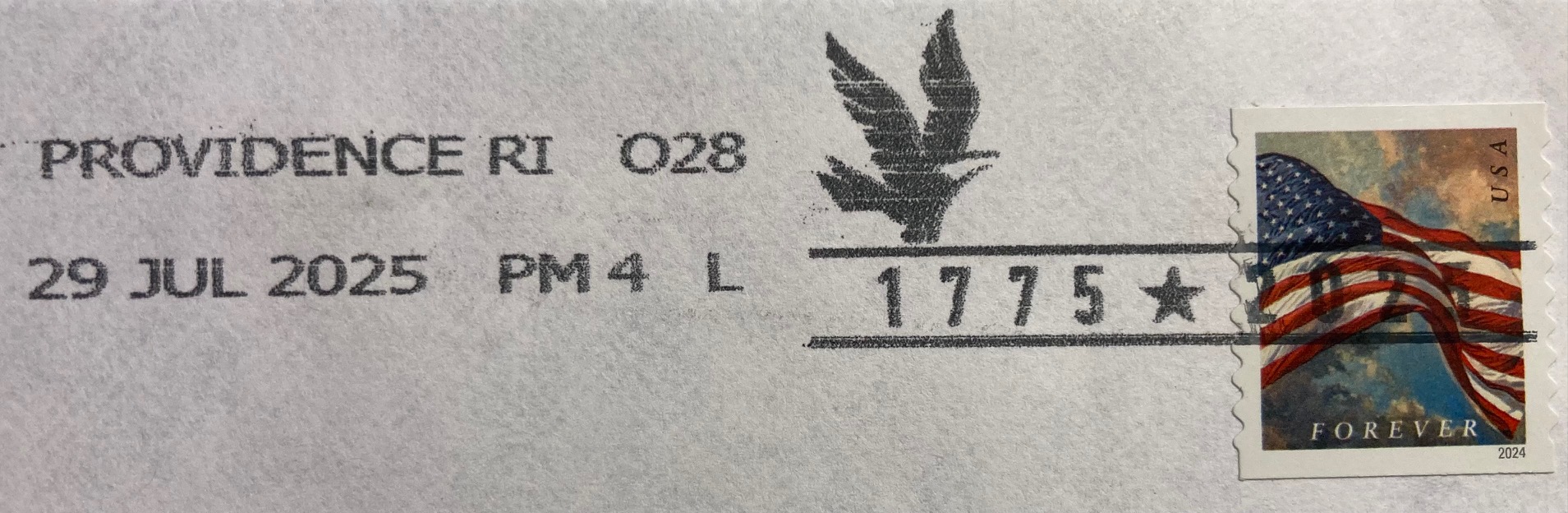

In the late 20th century, the time and place on standard North American postmarks appeared in a circular mark that contained the date and city where the letter was processed, followed by empty space and then wavy lines, bars, or a public service message that cancelled the stamp, as we can see in the early 1980s examples below (the “Please Mail Early for Christmas” cancellation appears atop a stamp from the popular US Transportation Coil series of the 1980s and 90s). This postmark convention continues today in the early 21st century, with time and place on the left and cancellation on the right; the mark in the last example celebrates the 250th anniversary of the beginning of the American Revolution.

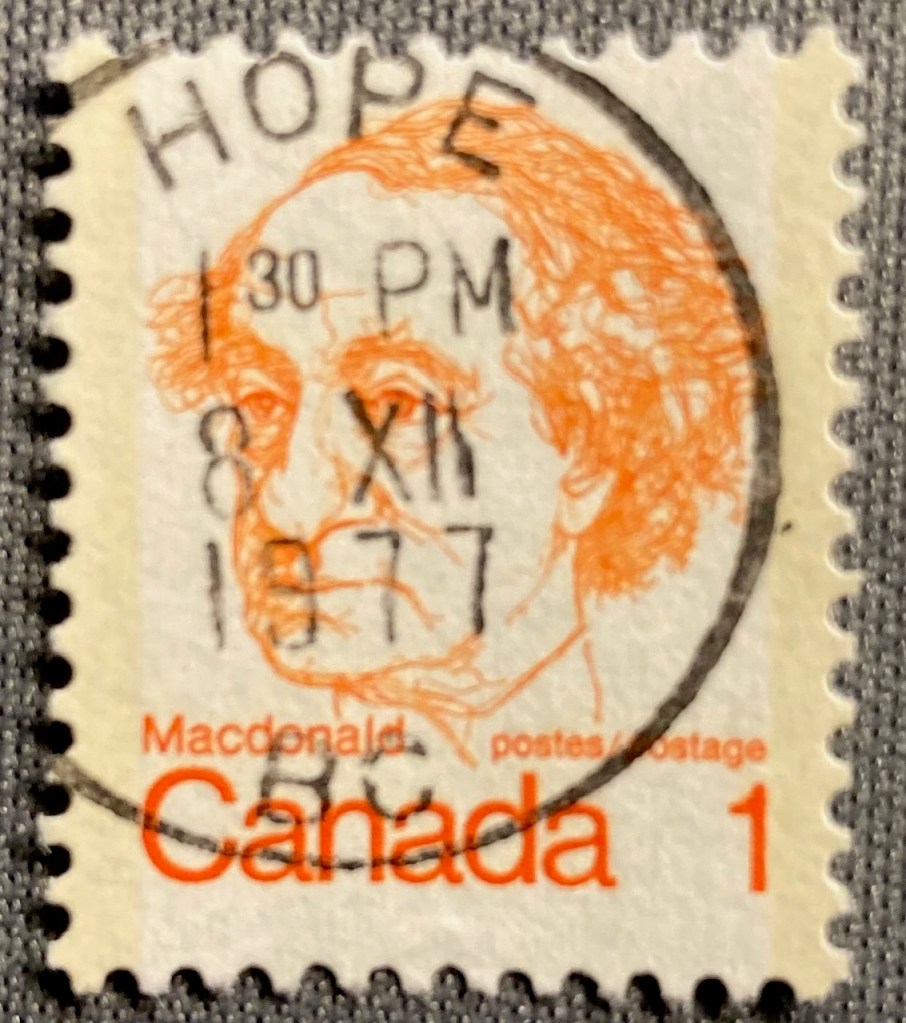

Given the placement of the marks, the date and place often don’t appear on these US and Canadian stamps; you would need a piece of the envelope to see the provenance. But sometimes you get lucky. This low denomination stamp was probably one of two or three stamps on its letter; given it’s position on the envelope the mark landed squarely on the prime minister. Hope is a virtue, and also a place in British Columbia where a letter was mailed on Dec 8, 1977 (December being the 12th month, XII in Roman numerals which Canada used on its postmarks)

If we go further back in time to periods before mail was processed mechanically, or to places that didn’t have this equipment, we begin to see more stamps that were cancelled by hand, and we’re more likely to see the origin and date marked on the stamp. Queen Elizabeth II appears with her father King George VI on a letter from Crawford Bay, BC on March 28, 1962. QE II is probably the most widely depicted person on postage stamps; this series is known as Canada’s Wildings, their main definitive stamp from the 1950s to early 60s. The photo was taken by Dorothy Wilding, whose photos were also used for the UK’s 1950s definitive stamps of the queen (which are known by collectors as The Wildings). I should add, “definitives” are the small, basic, and most widely printed stamps that countries issue. Think of stamps of the flag in the US, or the queen (or now, the king) in the UK and Canada (Canadians also employ their flag and the maple leaf quite a bit).

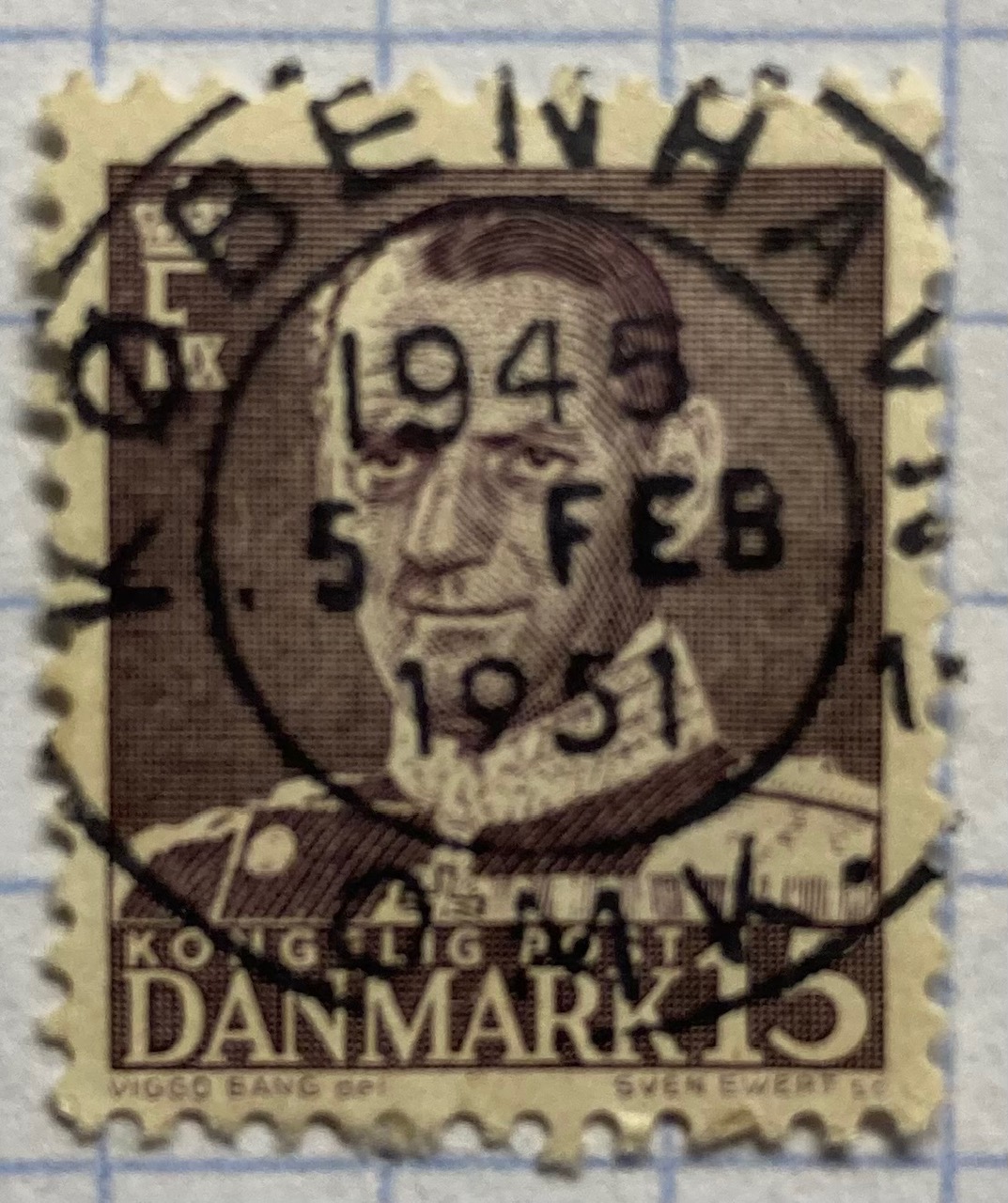

Postmarks vary over time and place with many countries having distinct cancellation styles, and where the markings may appear on the stamp itself. The examples below depict marks that “hit the spot”, on afternoons in 1954 in Kingston, Jamaica and 1982 in Pinetown, South Africa (ten miles from Durban). The marks on the Danish and Italian stamps are a bit larger than the stamps themselves, but we can still make out Kobenhavn (Copenhagen) in Denmark. The year is 1951; the 1945 at top is actually 19:45 hours as they use the 24-hour clock (7:45pm). Since the Coin of Syracuse (the definitive Italian stamp from the 1950s through the 70s – this one cancelled in 1972) is still on the envelope, we can see it originated in Montese, a town in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy.

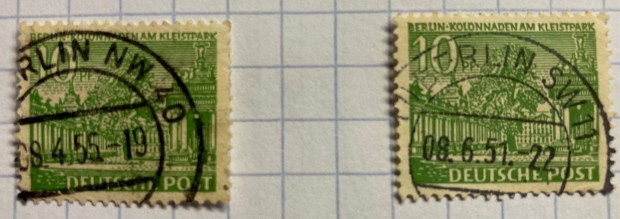

German stamps had a couple of distinctive marks in the mid 20th century, which often landed directly on the stamp. If you acquire enough of these you can assemble a collection that represents cities across the country. The 1930s examples below depict Paul Von Hindenburg, a WWI general and later president of the Weimar Republic. After WWII, Germany and the city of Berlin were divided into occupation zones; we can see examples from the Northwest and Southwest Berlin zones canceled in the 1950s.

The postmarks in these Latin American stamps incorporate their country of origin.

Back in North America, in the first half of the 20th century post offices issued pre-cancelled stamps that bore the mark of the city where they were distributed. Pre-cancelling was an early solution for saving time and money in processing large volumes of mail. In the US, you’ll see these on definitive stamps from the 1920s to the 1970s, particularly on the 4th Bureau Issues (1922-1930) (example of 4c Taft and 5c Teddy Roosevelt on the left), and the Presidential Series of 1938, known as the ‘Prexies”. This series was proposed by Franklin Roosevelt, who was an avid stamp collector, and it depicted every president from Washington to Coolidge. Given the wide range of stamps and denominations, they remained in circulation into the 1950s.

If you’re lucky, you can discover some interesting connections between the postmark and the subject depicted on the stamp, like this 4th Bureau, 1920s stamp of the Statue of Liberty, prominently pre-cancelled in New York.

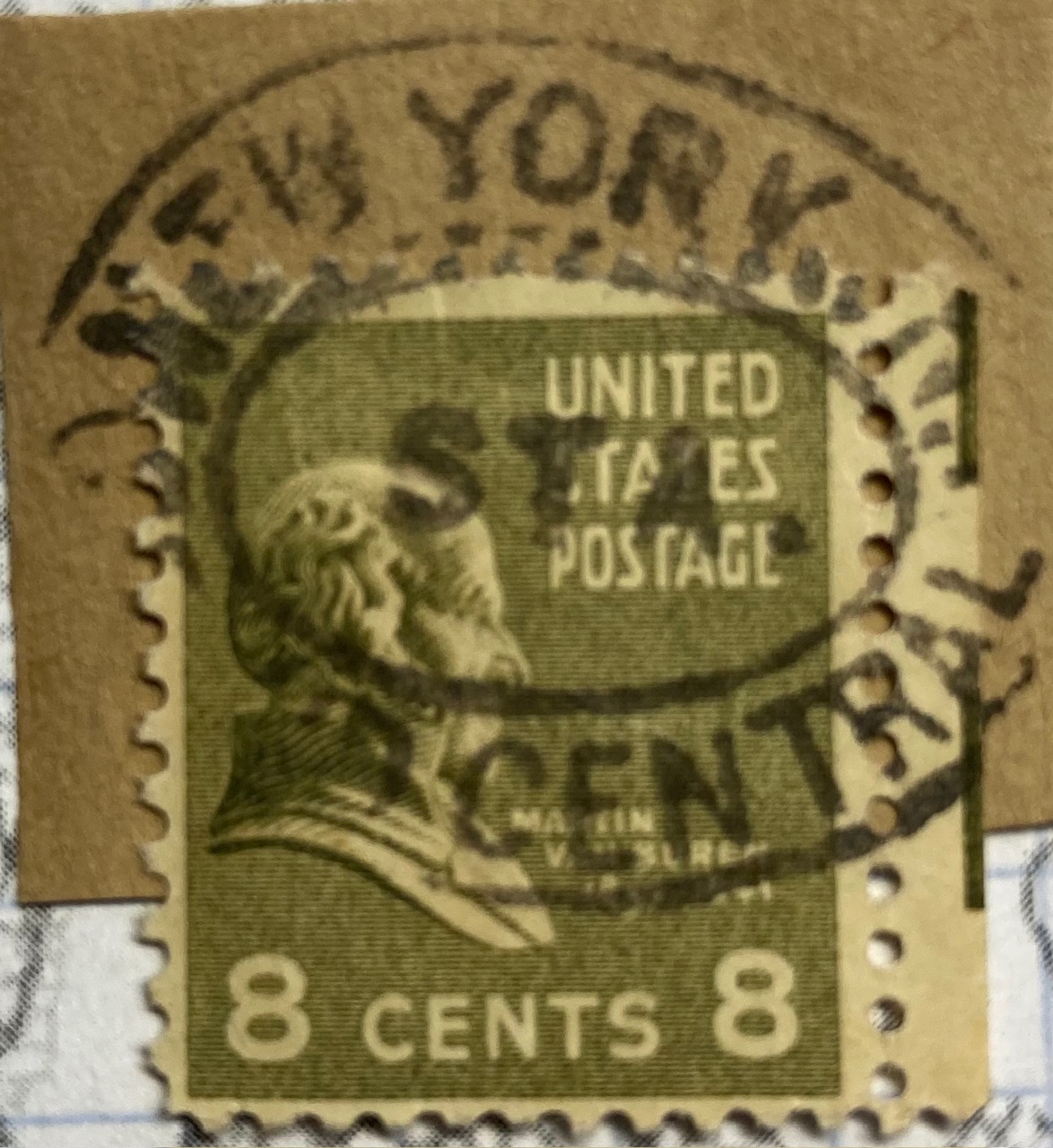

Mail was often transported by train, and train stations were key points where passengers would mail letters before and after traveling, and in some cases even on the train if there was a postal car. “Gare” is the French term for “station”, and we see examples from 1910 Belgium and 1985 France below. An example from Germany is marked Bahnpost (“station” or “train” mail) on board a Zug (“train”) that left Chemnitz early in the 20th century. Since I still had a portion of the envelope, we know the Prexie stamp of Martin Van Buren traveled through Grand Central Station in NYC, at some point in the mid 20th century.

Parts of the Address

Beyond the cancellation mark that provides time and origin of place, geography also appears in postmarks as exhortations from post offices to encourage letter writers to address mail correctly, so that it ends up at the right destination. The development of addressing systems was, in part, prompted by the need to get mail to locations quickly and accurately. This mid-20th century mark on a pair of John Adams Prexies reminds folks to include both the street and house number in the address.

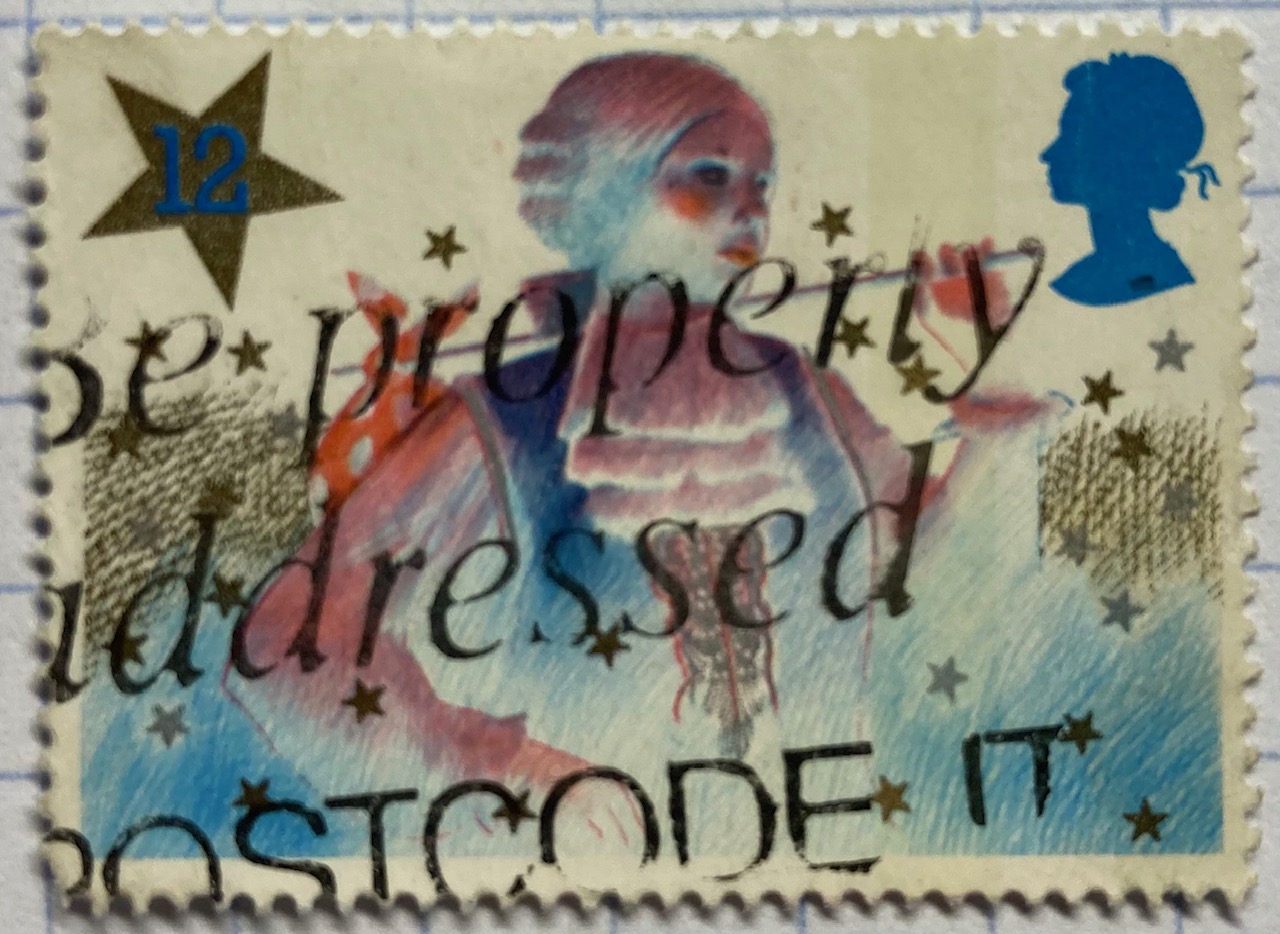

Postal codes were developed in the mid 20th century as unique identifiers to improve sorting and delivery, as the volume of mail kept increasing. The 1980s stamps below include an example from the US, where the ZIP Code or “Zone Improvement Plan” is the name of US postal code system (introduced in 1963). The USPS always wants you to use it. The other stamp comes from the UK, where the Royal Mail encourages you to “Be Properly Addressed” by adding your post code.

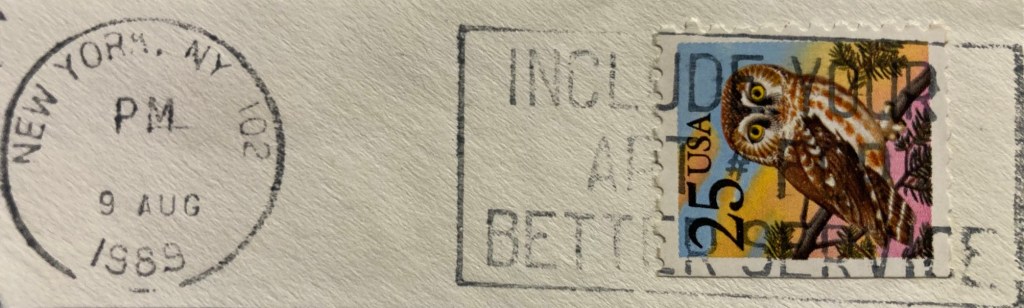

If you’ve ever lived in an apartment building, you’ve probably experienced the annoyance of not receiving letters and packages because the sender (or some computer system) failed to include the apartment number. This is particularly problematic in big cities like New York, so the post office regularly reminded folks with this special mark.

Celebrating Places in Postmarks

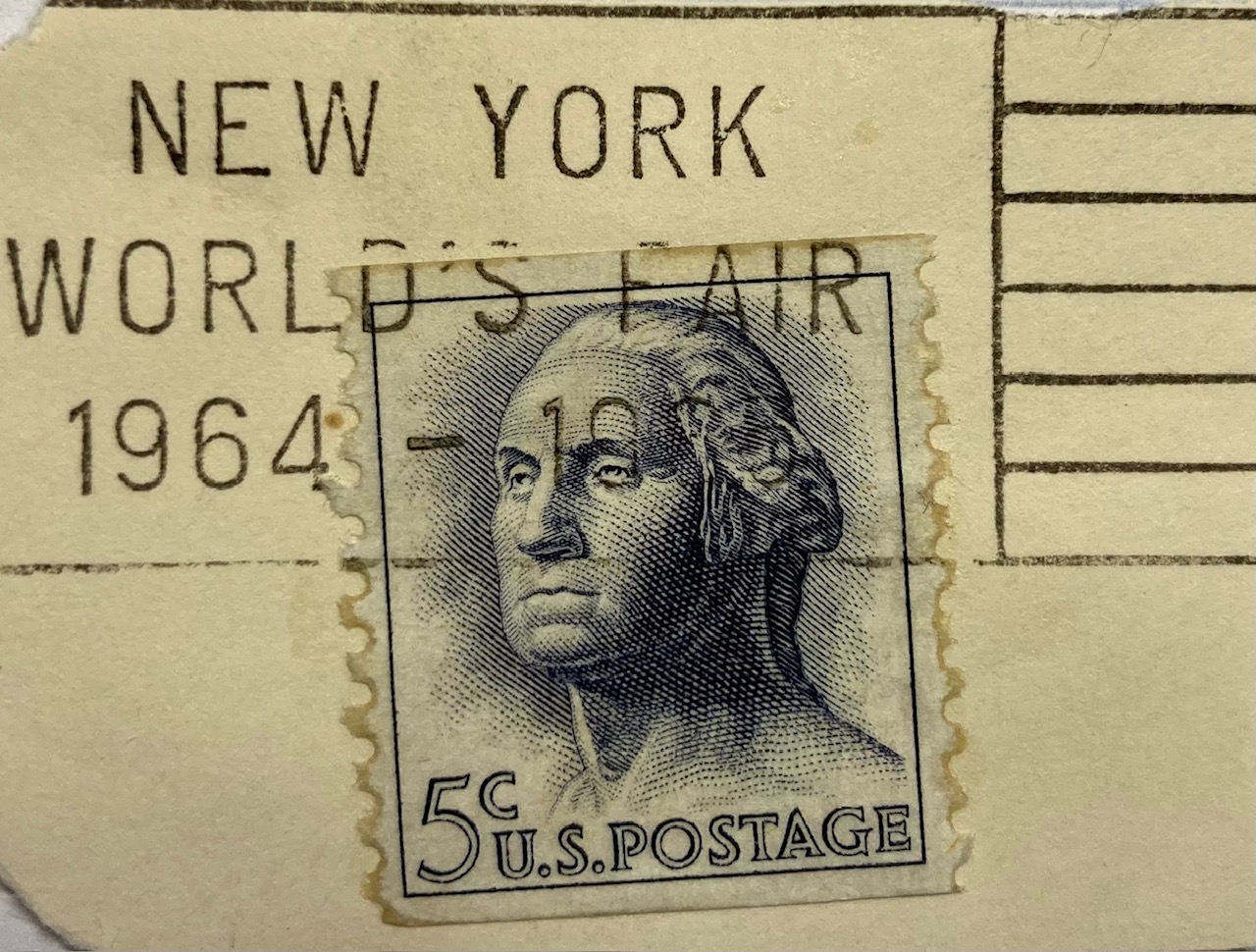

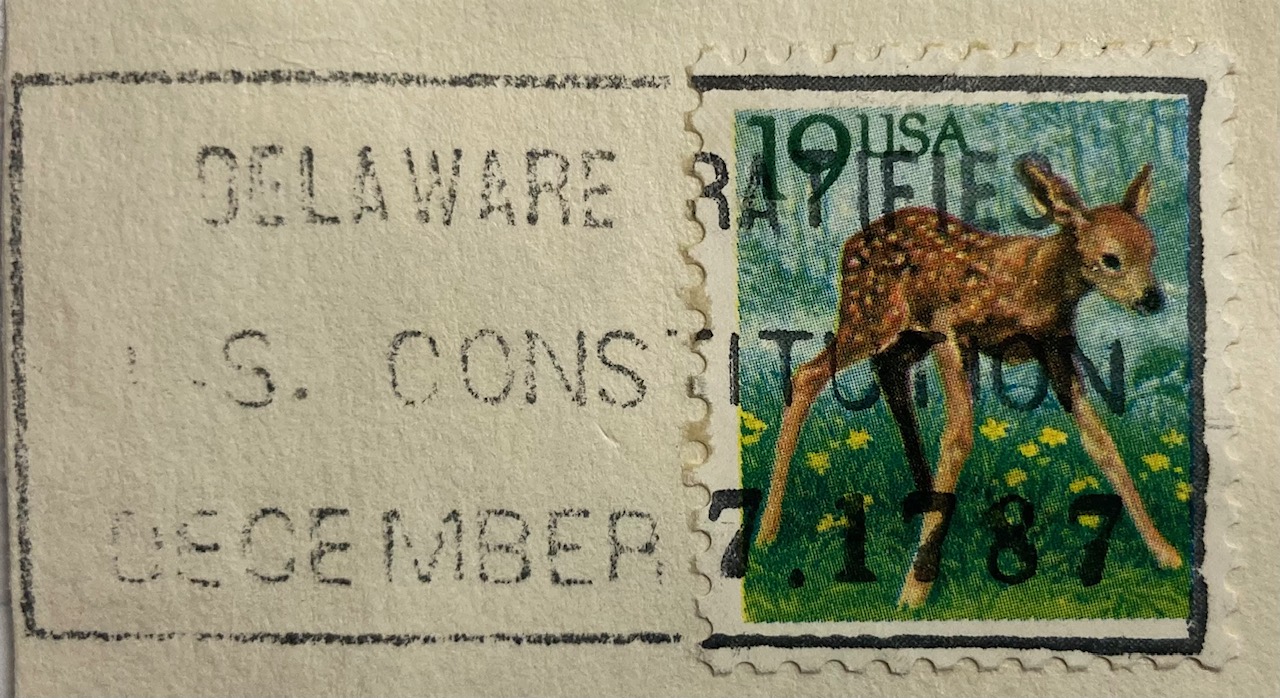

The most interesting examples of geography in postmarks are special, commemorative markings celebrating specific places and events tied to particular locales. Some of the marks have utilitarian designs like the ones below, commemorating the World’s Fair in New York in 1964 – 65, celebrating Delaware’s 200th anniversary of being the first state to ratify the Constitution, and promoting the burgeoning Research Triangle in North Carolina in the 1980s.

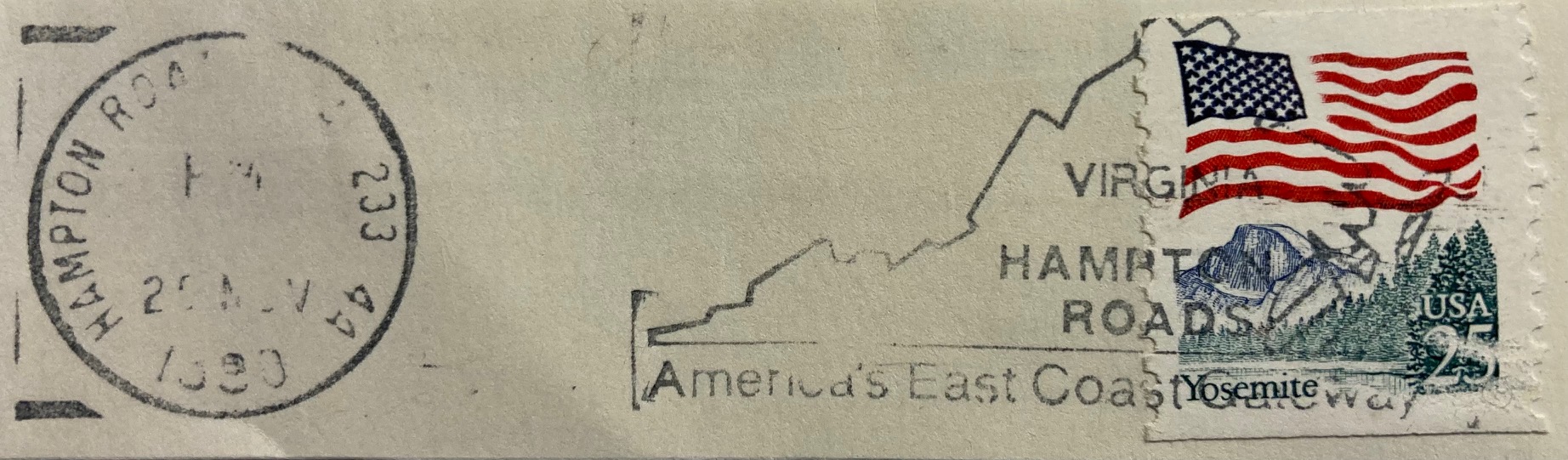

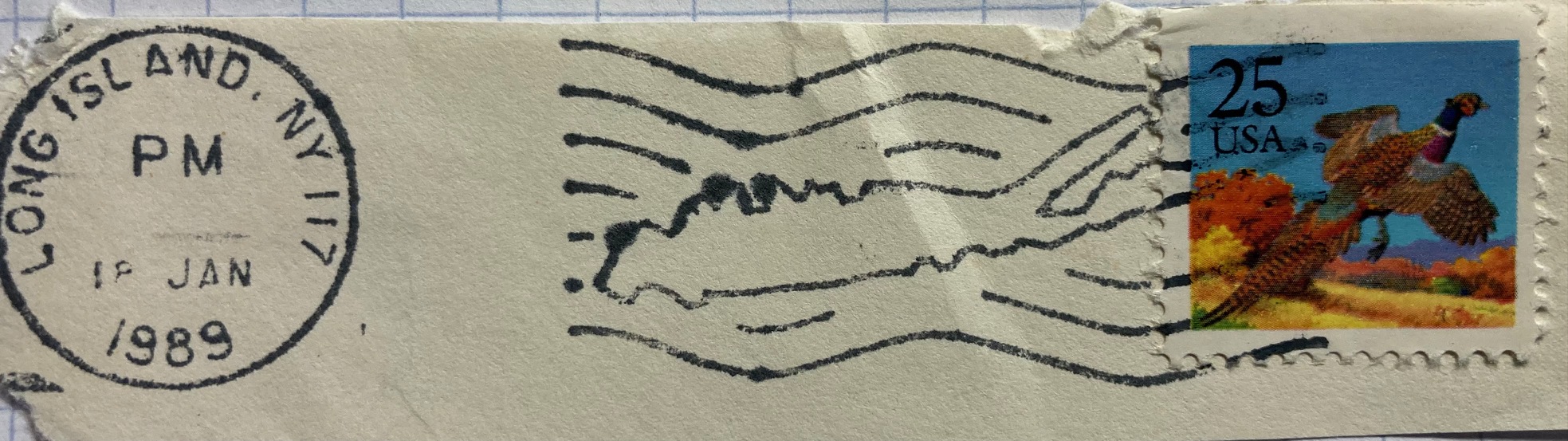

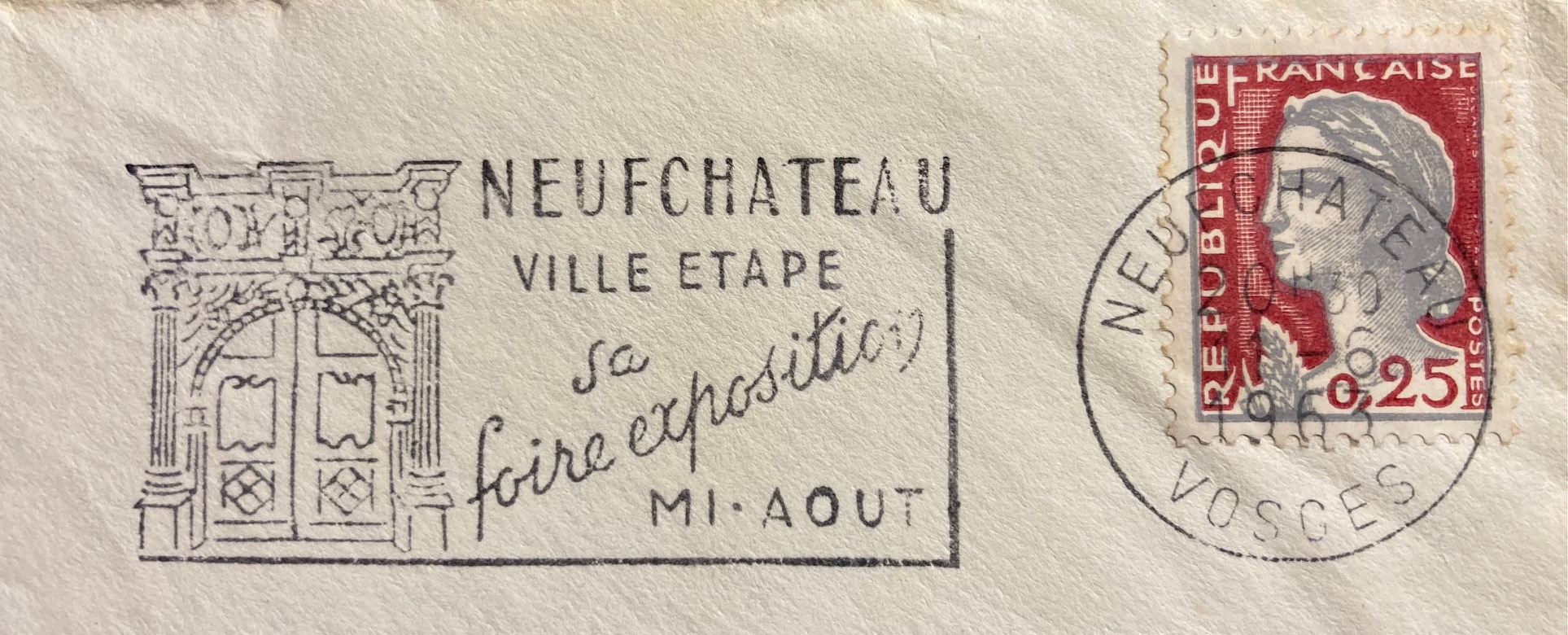

Others marks are fancier, depicting maps or places in the markings themselves. The examples below include a promotion for Hampton Roads in Virginia, and a stylized version of Long Island embedded in wavy cancellation lines. Most of the items I have are from the US, but you’ll find examples from around the world. The postal service in France has long created special markings to celebrate local and regional culture and history. This mark from the early 1960s celebrates an exhibition or trade fair in Neufchateau in northeastern France. For special markings like these, collectors will often save the entire envelope (in my case it was damaged, so I opted to clip out the marking and stamp). The stamp features Marianne, a legendary personification of the French republic who has appeared on definitive stamps there since the 1940s.

If you’ve acquired a bag of stamps you’ll get a mix that are on paper (clipped or torn from the envelope), or off paper (removed from the envelope by soaking in warm water, before the days of self adhesives). You often lose the message and provenance in these mixed bags, but are left with tantalizing clues, and funny quirks. The message on this 1970s Spanish stamp featuring long-time leader (aka dictator) Francisco Franco is unclear. He is shouting something about “districts” and “letters” in reference to the cities of Barcelona and Bilbao.

Did you know there were dinosaurs in Yosemite National Park? This brontosaurus was part of a larger marking that advertised the adventures of stamp collecting, which these US Korean War soldiers encourage you to do.

In Conclusion

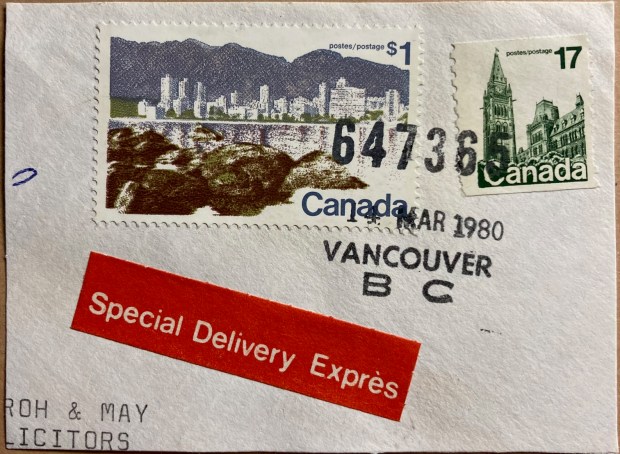

I hope you enjoyed this nerdy journey through the world of postmarks on stamps and their relation to geography. I’ll leave you with one final, strange fact that you may be unaware of. The lead image at the top of this post depicts a stamp of Vancouver’s skyline, that happened to be postmarked in Vancouver, Canada in March 1980. It’s always neat when you find these examples where the postmark and the stamp are linked. But did you know Vancouver glows in the dark? Countries began tagging stamps with fluorescence or phosphorescence in the mid 20th century, so machines could optically process mail. You can see them glow using special UV lamps – just be sure to wear protective eye wear (the bright yellow lines along the edges of the stamp are the tags).

You must be logged in to post a comment.