The first draft is finished and I sent my book off for review earlier this month, and I’ve been back to work full-time for two months now. It’s been a difficult transition, so I thought I’d write a more lighthearted post this month about imaginary geographic worlds (as luck would have it, the Geo NYC Meetup group is discussing fictional mapping next week).

I’ve always enjoyed top-down simulation games; I still have my original copy of SimCity from 1989, in the box with the diskettes. More recently, I started playing a top-down, world-exploration, operations management, logistical simulator game called Factorio. The premise is you are the sole survivor of a team of scientists and engineers who have crash landed on an unexplored world. Using the scrap metal of your ship, a few simple tools, and the abundant resources on the planet, your goal is to build a rocket to launch a satellite into space to alert the crew of a successive spaceship of your presence. Scattered across the planet are concentrations of resources: water, trees (for wood), stone, iron ore, copper ore, oil, coal, and uranium. With an ax and a few scavenged plates from the ship, you begin by building a stone furnace for smelting metals. You use your ax to mine some stone to build the furnace, some iron for smelting, and some coal for fuel. Once you’ve smelted some metal you can construct a drill to mine the materials and insert them into the smelter automatically.

Smelting the ore converts it into refined material: stone to bricks, iron ore to iron plates, and copper ore to copper plates. Initially you can take these materials and manually craft them to make products: iron plates become iron gear wheels, copper plates become copper wire, which in turn can be crafted to create higher order parts like electronic circuits and finished machine products. Ultimately you’ll construct assembly plants that take the necessary materials and build the products for you, and the outputs can be used as inputs for other products.

Mining ore

Smelting ore to plates

Assembling products

The game becomes a logistical puzzle, where you mine ores from various deposits and move them to be smelted, and then move the refined materials to different assembly plants to create higher-order products. You transport everything using conveyor belts and inserters, which grab materials from belts and insert them into the smelters, assemblers, and other structures. You construct pumps, boilers, and steam engines powered by coal or wood to generate electricity to power the entire factory, and in order to keep developing higher-order goods you combine certain materials to produce “science”; little colorful beakers of liquid that you move on belts to laboratories to keep research humming.

As the game and your research progresses you develop technology that allows you to better explore the world and access additional resources, as you’ll eventually deplete the original deposits near the factory. You can develop solar and nuclear power as cleaner electricity alternatives, drill and refine oil to create fuels and plastics, build cars to explore the landscape, and construct railroads to transport more distant materials to your base. As your factory expands you have to grapple with the logistical hurdles of moving products created at disparate ends of the plant together in order to create new products, forcing you to either plan ahead or reconfigure your layout as time passes (or build some drones to fly the materials around). The clock is always ticking as the game is played in real time (it’s not turn-based).

Main Factorio screen showing portion of a factory and map layout

At some point you face a new problem: you are not alone on this planet. There are some large, scary-looking insect creatures living there that don’t like all the pollution that’s coming from your factory, and they don’t particularly like you. Once they become irritated enough they attack and chew up your factory, and you along with it. Sadly there is no negotiating with them (they’re not sentient), so some of your attention and resources must be spent on weapons. You can take a purely defensive approach, building walls and gun turrets to protect your base as well as armor and shields to protect yourself. Or you can barrel out in a tank or use artillery to destroy them as they encroach on your operations. You can also develop cleaner, less polluting technologies to irritate them less.

An additional challenge is that the game keeps changing. Even though it’s been out for several years Factorio is still in a beta phase, but given it’s maturity and update cycle it’s super stable. The developers are part of a small company in the Czech Republic who focus primarily on this game. Factorio is available for purchase via their website and via Steam for all operating systems, and has been downloaded over a millions of times. The fanatical fan base appreciates the ability to mod practically every aspect of the game, and they form a community that’s crucial to the game’s development through testing and feedback. Factorio is definitely a member of a new generation of games where part of the challenge is learning how to play it. I’ve crawled through the extensive wiki, scoured Reddit for advice, and watched several YouTube series to figure out how it works.

Regardless of how many times you’ve played it, there is always something new to tinker with. Many players enjoy the engineering and mathematical side of the game. Their goal is to build the most efficient system, perfectly balance inputs and outputs, and create the best ratios for production. Others go for scale, building the largest possible factory with the most throughput. There are railroaders who enjoy building the trains, and warriors who focus on combat with the voracious bugs. Beyond building the rocket, the game has a number of challenges that players attempt to master, and it can be played solo or multiplayer for gamers who want to work together or simply explore each other’s layouts and solutions.

As a geographer, I enjoy the actual worlds themselves and the unique challenge each environment presents. While you can create blueprints and use the same design for a railroad station or solar power generator over and over again, you’re forced to change your overall factory layout based on the location of resources and configuration of the terrain. Prior to launching a new game, you specify the general size, frequency, and richness of resources, trees, water, and enemy bugs, and you can keep generating maps until you find one you like. While many of the efficiency aficionados want flat playing surfaces, I enjoy the complexity of fitting your factory in around the oceans and forests, and the challenge of exploring and shipping in materials from far flung places.

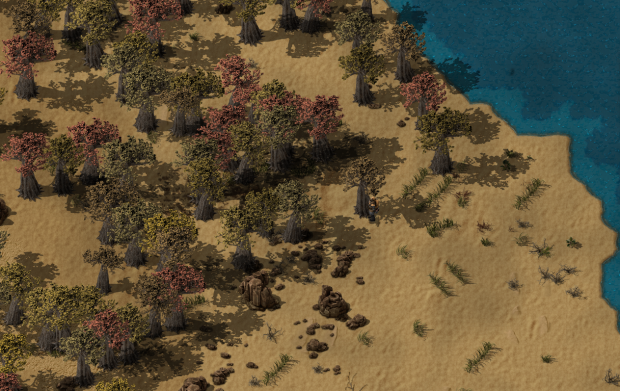

The world itself is quite beautiful. The developers provide extensive details about the development and inner-workings of the game, including the processes for generating logical and realistic looking landscapes. There are lush deciduous forests in vibrant autumn colors, desert wastelands strewn with rocks, and clusters of baobab-like trees on the dry plains. Even though they’re just bits and bytes I limit what I harvest, because I hate chopping them down. Unlike the real world, mining ore is much less destructive and the material is simply scraped off the surface, leaving unblemished soil behind. A finite portion of the world is visible on the map when you begin the game, and the surrounding area is cloaked in darkness. You can reveal more of the terrain by building radar stations at your base, and can explore on foot or go further afield once you’ve constructed vehicles. The world has no end, and stretches into infinity.

Factorio has sparked my curiosity in unexpected ways. As I’m mining ores and moving them into smelters to produce metals, I started to wonder: what is smelting anyway? How do you actually extract metals from rocks? My exposure to chemistry was limited to my junior year of high school where I struggled with balancing formulas and memorizing the periodic table. Fortunately I discovered some fascinating books and videos that made the subject engaging. Material scientist Mark Miodownik’s Stuff Matters: Exploring the Marvelous Materials That Shape Our Man-Made World, is an accessible, informative, and often hilarious exploration of the materials we use everyday. You’ll learn the basic chemistry behind paper, iron, ceramics, even chocolate! Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to Zinc by Hugh Aldersey-Williams is perfect if you want to learn some basics about chemistry and material science from a historical science perspective. NOVA aired a solid three-part series a few years back called Treasures of the Earth that revealed the secrets behind gems, metals, and power sources.

I resisted the temptation to play for the year I was on sabbatical, as it’s too easy to get sucked into it. A few hours here and there throughout a month, and by the time I launch that rocket into space 30 hours have gone by! Initially I feel a bit guilty, sinking so much time into a game. But when you consider how much time the average person spends watching TV or looking at stupid stuff on their phone (4 hours and 2.5 hours respectively, EVERY DAY!), enjoying the occasional game that challenges your mind and sparks your imagination is a good alternative. Similar to the Minecraft phenomena, I think it has great potential as an educational tool for learning about logistics, planning, geology and materials science, and engineering. And for the geographers out there, there are infinite worlds to explore.

You must be logged in to post a comment.