I’m fortunate to be on sabbatical for much of this summer, and am working on a project where I’m measuring the effectiveness of comparing census American Community Survey estimates over time. I’ve written a lot of Python code over the past six weeks, and thought I’d share some general tips for working with bigger datasets.

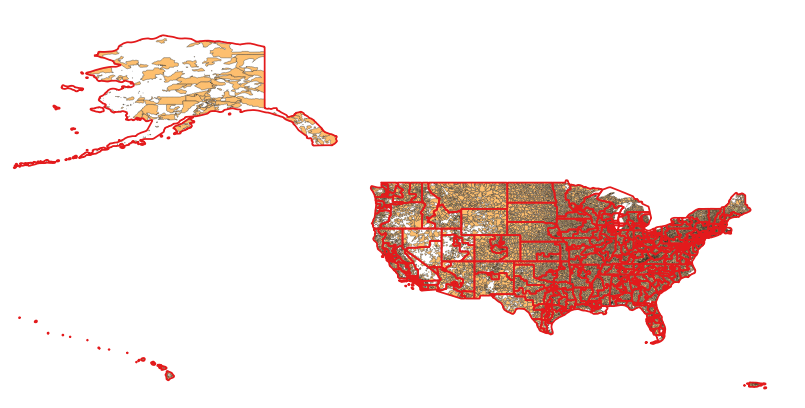

For my project, I’m looking at 317 variables stored in 25 tables for over 406,000 individual geographic areas; approximately 129.5 million data points. Multiply that by two, as I’m comparing two time periods. While this wouldn’t fall into the realm of what data scientists would consider as ‘big data’, it is big enough that you have to think strategically about how handle it, so you don’t run out of memory or have to wait hours while tasks grind away. While you could take advantage of parallel processing, or find access to a high performance computer, with this amount of data you can stick with a decent laptop, if you take steps to ensure that it doesn’t go kaput.

While the following suggestions may seem obvious to experienced programmers, it should be helpful to novices. I work with a lot of students whose exposure to Python programming is using Google Colab with Pandas. While that’s a fine place to start, the basic approaches you learn in an intro course will fall flat once you start working with datasets that are this big.

- Don’t use a notebook. Ipython notebooks like Jupyter or Colab are popular, and are great for doing iterative analysis, visualization, and annotation of your work. But they run via web browsers which introduce extra overhead memory-wise. Iterative notebooks are unnecessary if you’re processing lots of data and don’t need to see step by step results. Use a traditional development environment instead (Spyder is my favorite – see the pic in this post’s header).

- Don’t rely so much on Pandas DataFrames. They offer convenience as you can explicitly reference rows and columns, and reading and writing data to and from files is straightforward. But DataFrames can hog memory, and processing them can be inefficient (depending on what you’re doing). Instead of loading all your data from a file into a frame, and then making a copy of it where you filter out records you don’t need, it’s more efficient to read a file line by line and omit records while reading. Appending records to a DataFrame one at a time is terribly slow. Instead, use Python’s basic CSV module for reading and append records to nested lists. When you reach the point where a DataFrame would be easier for subsequent steps, you can convert the nested list to a frame. The basic Python data structures – lists, dictionaries, and sets – give you a lot of power at less cost. Novices would benefit from learning how to use these structures effectively, rather than relying on DataFrames for everything. Case in point: after loading a csv file with 406,000 records and 49 columns into a Pandas DataFrame, the frame consumed 240 MB of memory. Loading that same file with the csv module into a nested list, the list consumed about 3 MB.

Reads a file, skips the header row, adds a key / value pair to a dictionary for each row using the first and second value (assuming the key value is unique).

import os, csv

keep_ids={}

with open(recskeep_file,'r') as csv_file:

reader=csv.reader(csv_file,delimiter='\t')

next(reader)

for row in reader:

keep_ids[row[0]]=row[1]

Or, save all the records as a list in a nested list, while keeping the header row in a separate list.

records=[]

with open(recskeep_file,'r') as csv_file:

reader=csv.reader(csv_file,delimiter='\t')

header=next(reader)

for row in reader:

records.append(row)]

- Delete big variables when you’re done with them. The files I was reading were segmented in twos: one file for estimates, and one for margins of error for those same estimates. I read each into separate, nested lists while filtering for records I wanted. I had to associate each set with a header row, filter by columns, and then join the two together. Arguably that part was easier to do with DataFrames, so at that stage I read both into separate frames, filtered by column, and joined the two. Once I had the joined frame as a distinct copy, I deleted the two individual frames to save memory.

- Take out the garbage. Python automatically frees up memory when it can, but you can force the issue by emptying deleted objects from memory by calling the garbage collection module. After I deleted the two DataFrames in the previous step, I explicitly called gc.collect() to free up the space.

...

del est_df

del moe_df

gc.collect()

- Write as you read. There’s no way I could read all my data in and hold it in memory before writing it all out. Instead I had to iterate – in my case the data is segmented by data tables, which were logical collections of variables. After I read and processed one table, I wrote it out as a file, then moved on to the next one. The variable that held the table was overwritten each time by the next table, and never grew in size beyond the table I was actively processing.

- Take a break. You can use the sleep module to build in brief pauses between big operations. This can give your program time to “catch up”, finishing one task and freeing up some juice before proceeding to the next one.

time.sleep(3)

- Write several small scripts, not one big one. The process for reading, processing, and writing my files was going to be one of the longer processes that I had to run. It’s also one that I’d likely not have to repeat if all went well. In contrast, there were subsequent analytical tasks that I knew would require a lot of back and forth, and revision. So I wrote several scripts to handle individual parts of the process, to avoid having to repeat a lot of long, unnecessary tasks.

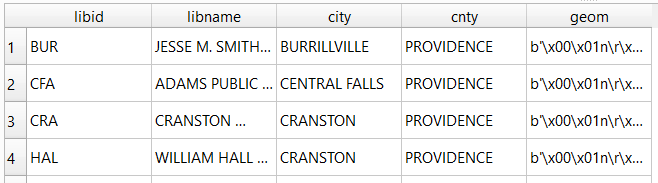

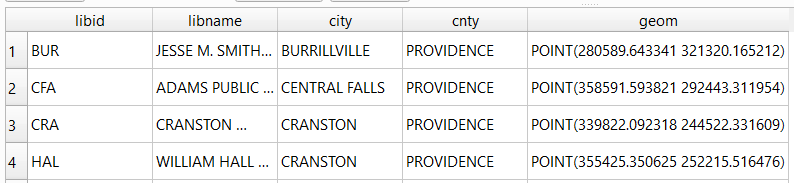

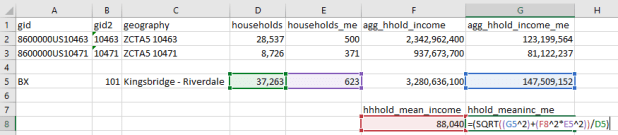

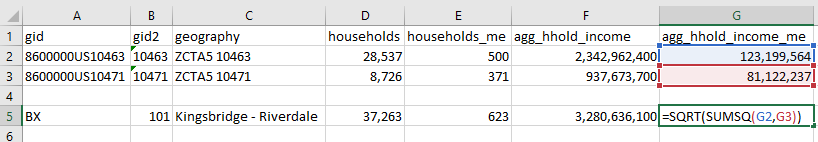

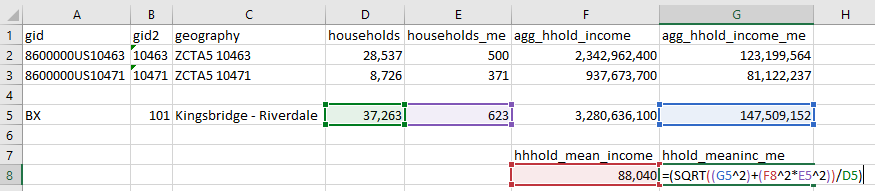

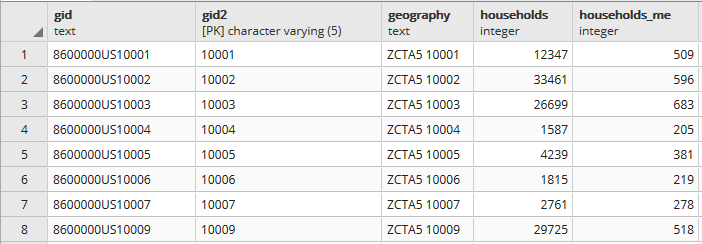

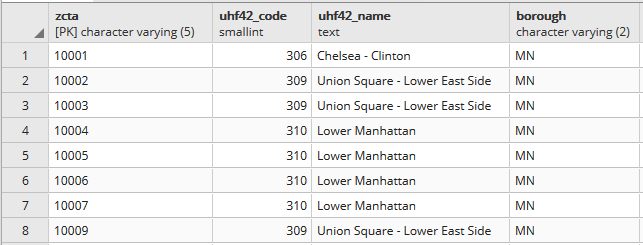

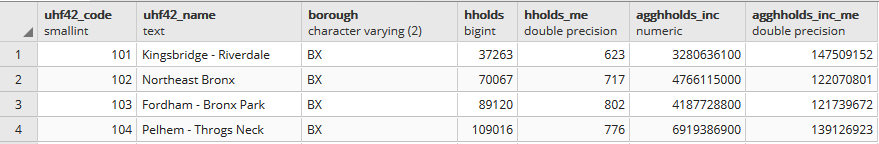

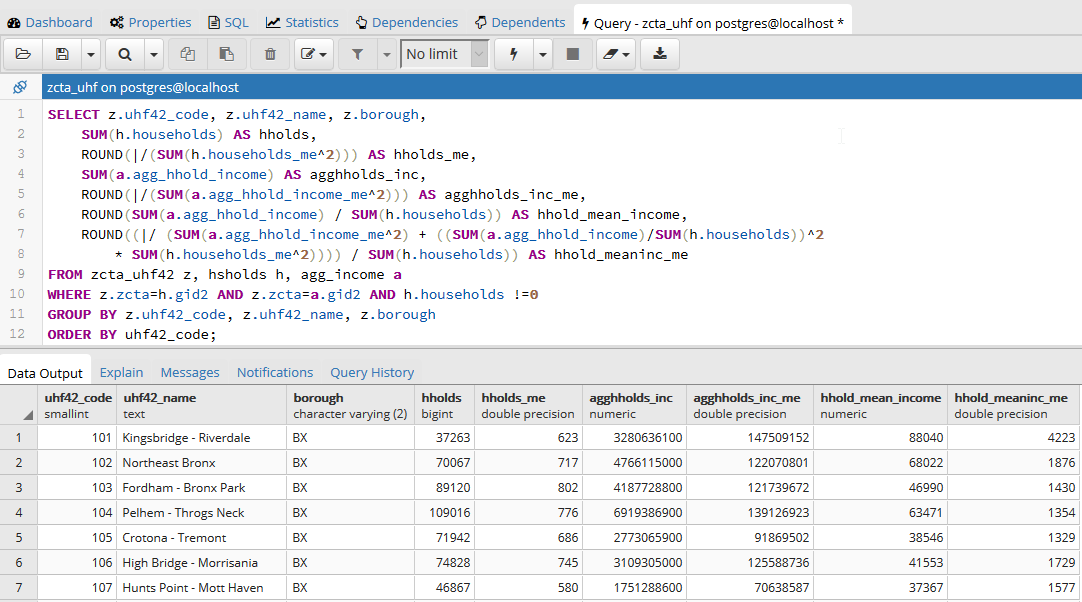

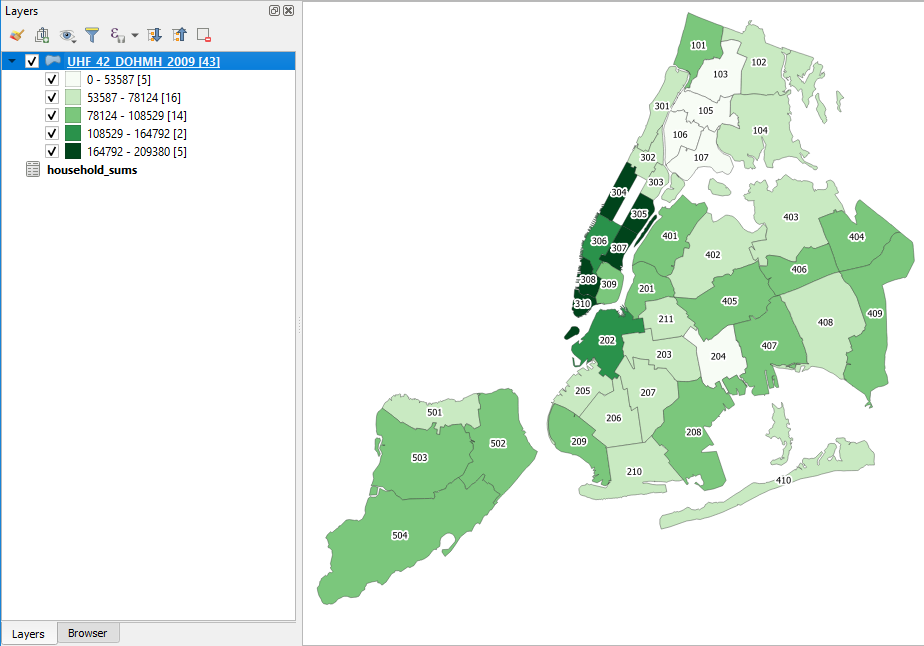

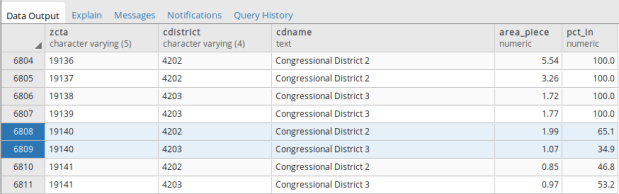

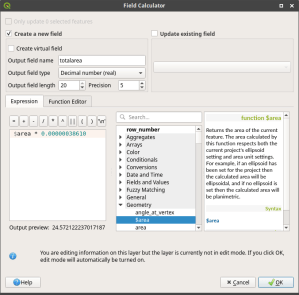

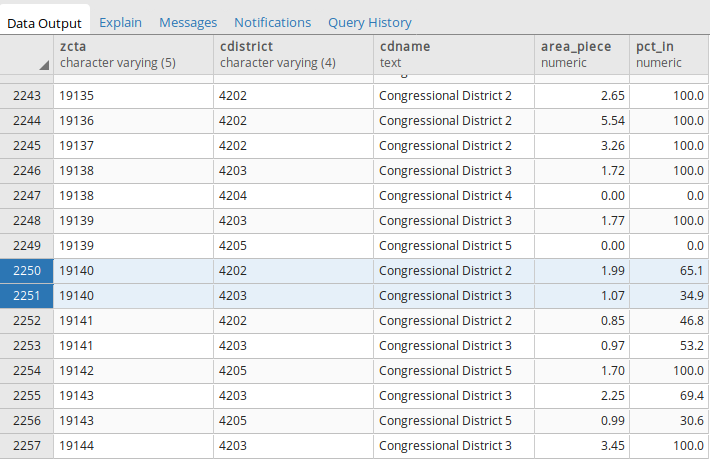

- Lean on a database for heavy stuff. Relational databases can handle large, structured data more efficiently compared to scripts reading data from text files. I installed PostgreSQL on my laptop to operate as a localhost database server. After I created my filtered, processed CSV files, I wrote a second program that loaded them into the database using Psycopg2, a Python module that interacts with PostgreSQL (this is a good tutorial that demonstrates how it works). SQL statements can be long, but you can use Python to iteratively write the statements for you, by building strings and filling placeholders in with the format method. This gives you two options. Option 1, you execute the SQL statements from within Python. This is what I did when I loaded my processed CSV files; I used Python to iterate and read the files into memory, wrote CREATE TABLE and INSERT statements in the script, and then inserted the data from Python’s data structures into the database. Option 2, is you can use Python to write a SQL transaction statement, save the transaction as a SQL text file, and then load it in the database and run it. I followed this approach later in my process, where I had to iterate through two sets of 25 tables for each year, and perform calculations to create a host of new variables. It was much quicker to do these operations within the database rather than have Python do them, and executing the SQL script as a separate process made it easier for me to debug problems.

Connect to a database, save SQL statement as a string, loops through a list of variables IDs, and for each variable format the string by passing the values in as parameters, execute the statement and fetch the result – fetchone() in this case, but could also fetchmany():

# Database connection parameters

pgdb='acs_timeseries'

pguser='postgres'

pgpswd='password'

pgport='5432'

pghost='localhost'

pgschema='public'

conpg = psycopg2.connect(database=pgdb, user=pguser, password=pgpswd,

host=pghost, port=pgport)

curpg=conpg.cursor()

sql_varname="SELECT var_lbl from acs{}_variables_mod WHERE var_id='{}'"

year='2019'

for v in varids:

# Get labels associated with variables

qvarname=sql_varname.format(year, v)

curpg.execute(qvarname)

vname=curpg.fetchone()[0]

... #do stuff...

curpg.close()

- When using Psycopg2, don’t use the executemany() function. When performing an INSERT statement, you can have the module executeone() statement at a time, or executemany(). But the latter was excruciatingly slow – in my case it ran overnight before it finished. Instead I found this trick called mogrify, where you convert your INSERT arguments into one enormous string, and pass that to the mogrify() function. This was lightning fast, but because the text string is massive I ran out of memory if my tables were too big. My solution was to split tables in half if the number of columns exceeded a certain number, and pass them in one after the other.

- Use the database and script for what they do best. Once I finished my processing, I was ready to begin analyzing. I needed to do several different cross-tabulations on the entire dataset, which was segmented into 25 tables. PostgreSQL is able to summarize data quickly, but it would be cumbersome to union all these tables together, and calculating percent totals in SQL for groups of data is a pain. Python with Pandas would be much better at the latter, but there’s no way I could load a giant flat file of my data into Python to use as the basis for all my summaries. So, I figured out the minimal level of grouping that I would need to do, which would still allow me to run summaries on the output for different combinations of groups (i.e. in total and by types of geography, tables, types of variables, and by variables). I used Python to write and execute GROUP BY statements in the database, iterating over each table and appending the result to a nested list, where one record represented a summary count for a variable by table and geography type. This gave me a manageable number of records. Since the GROUP BY operation took some time, I did that in one script to produce output files. Creating different summaries and reports was a more iterative process that required many revisions, but was quick to execute, so I performed those operations in a subsequent script.

Lastly, while writing and perfecting your script, run it against a sample of your data and not the entire dataset! This will save you time and needless frustration. If I have to iterate through hundreds of files, I’ll begin by creating a list that has a couple of file names in it and iterate over those. If I have a giant nested list of records to loop through, I’ll take a slice and just go through the first ten. Once I’m confident that all is well, then I’ll go back and make changes to execute the program on everything.

You must be logged in to post a comment.